Black teachers: How to recruit them and make them stay

Lessons in higher education: What California can learn

Keeping California public university options open

Superintendents: Well-paid and walking away

The debt to degree connection

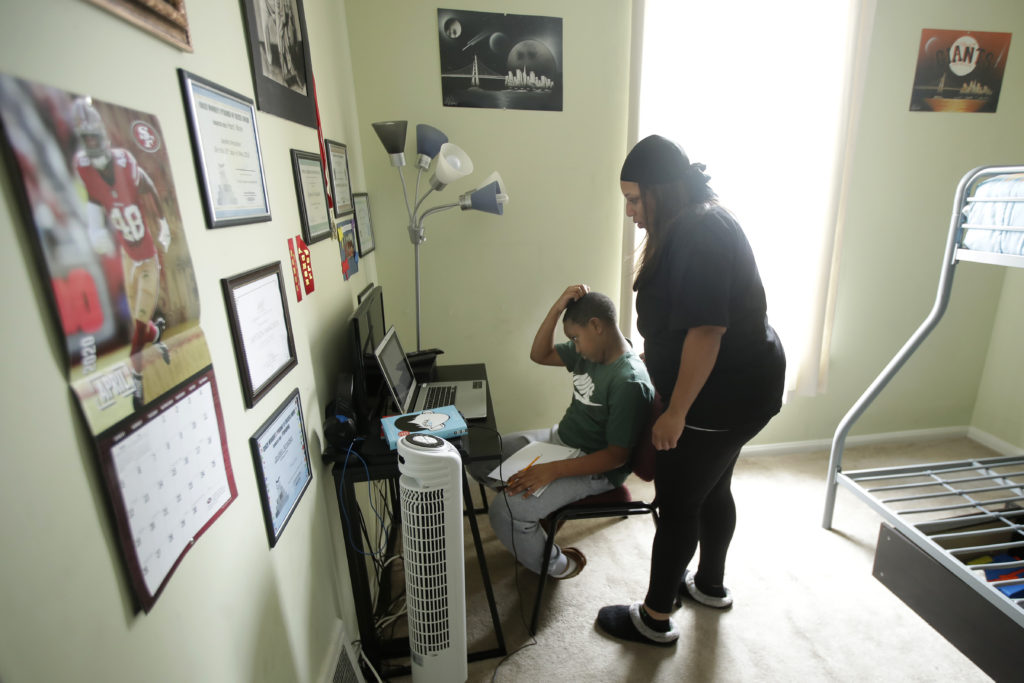

College in prison: How earning a degree can lead to a new life

While many high schools and middle schools adopted pass-fail grading at the start of the pandemic in order to hold students harmless as they adjusted to distance learning, districts have largely reverted back to the traditional A-to-F system.

But now that students are receiving their fall progress reports, it appears as though in at least some districts, many students’ grades are slipping. Los Angeles Unified Superintendent Austin Beutner announced Monday that the number of middle school and high school students receiving Ds and Fs so far this year has increased compared to last year. In Sonoma County, the number of high school students failing classes is so much higher than previous years that Steven Herrington, the county schools superintendent, convened a summit of district leaders last week to discuss the issue, and will meet again this Thursday.

According to the Bay Area News Group, 37% of high school students in the county had at least one failing grade compared with 27% at the same time last year. The number of high school students at Healdsburg Unified failing one of their classes, for example, thus far has nearly doubled compared to the fall of 2019.

Several districts around the state have sought to avoid a drop in grades by modifying their pre-pandemic grading policies to give students some leeway to help deal with the challenges of learning from home. In some districts, students won’t be docked for missing class or turning in work late, and participation won’t be part of their grades. Others are also doing more to notify parents if a student is at risk of failing.

State law doesn’t require districts to go back to letter grades. The set of standards approved by the Legislature in June only requires schools to track student participation and provide feedback to parents and guardians on students’ academic progress.

The return to letter grades this fall appears to have been influenced by the University of California and California State University’s decision to no longer accept pass/fail or credit/no credit grades earned by high school students this school year when or if they apply for admission.

Also, some educators say letter grades have proven to be an effective way to motivate students and gauge how well they are mastering a curriculum.

The California Department of Education doesn’t track districts’ grading policies, so it doesn’t know how many districts have returned to an A-F grading system. However, California School Boards Association spokesman Troy Flint said it appears as though almost every district in California that wasn’t doing A-F grading before is doing it now.

In the spring, CDE advised districts to amend their grading policies so that students wouldn’t receive grades lower than what they were before the pandemic forced districts to close campuses. The idea was to offer relief to students who didn’t have proper access to the technology to learn online, as well as those struggling to keep up with their schoolwork while dealing with stresses related to Covid-19.

Some districts kept the letter grades for students the same as they had earned before, while other districts eliminated letter grades in favor of pass/fail or credit/no credit systems.

For their part, the UC and CSU systems agreed to accept pass/fail or credit/no credit for winter, spring and summer 2020, including the college preparatory A-G course sequence required for admission to the university systems. But that waiver ended at the close of the last school year, and UC and CSU chose not to extend it.

Representatives from the UC wouldn’t explain why they came to that decision, but they said they may consider reinstating the waiver depending on how the pandemic further disrupts education. CSU spokesman Michael Uhlenkamp said they are not extending the waiver to this year since schools had time over summer to prepare for virtual instruction and to work with teachers on grading. CSU also wanted to align with the University of California system, he said.

With pass/fail grading essentially off the table, some districts are adapting their grading policies and guidance for teachers for this year to minimize the impact on students’ report cards.

West Contra Costa Unified decided in September to not penalize students for late work or unexcused absences; San Diego Unified adopted a similar policy Oct. 13. Long Beach Unified has called on its teachers to keep homework to a minimum, not have it graded and not give out Fs on assignments, though the district allows teacher discretion on grading.

“We’re trying to work within the A-F system to create as much flexibility as possible,” West Contra Costa Unified superintendent Matthew Duffy said at the September school board meeting in which the new grading policy was approved.

Teachers in many districts, including West Contra Costa Unified, are giving written feedback instead of letter grades for transitional kindergarten, kindergarten and elementary students.

Teachers will accept work within five days of the due date without penalty; students may also advocate for more time with their teachers. Teachers also won’t give “zero” grades for missing work — the work will instead be marked “missing” until completed.

Audra “Golddie” Williams, whose child is a senior at El Cerrito High School, said at the meeting that she “greatly appreciates” the protections, since her child and others are experiencing stresses they have never experienced before.

In the spring, Los Angeles Unified — the largest school district in the state — had adopted a policy that ensured no students would receive an “F” grade, and that students’ grades would not drop lower than what they were at the start of the pandemic.

This year, “F” grades are back on the table, but with conditions. A teacher must make several attempts to contact the student and their family to offer make up assignments, extra tutoring or other academic support. The teacher must also collaborate with academic counselors or other school staff and consult with the school site administrator before giving out an “F.”

The Newport-Mesa School District, which serves the cities of Newport Beach and Costa Mesa, also took away failing grades in the spring. In their system, students would either get an A, B, or C, or an “incomplete” and be given the opportunity to make up the credit over the summer. This year, the district reinstated Ds and Fs, district spokeswoman Annette Franco said.

The district is also calling on teachers to “show some grace” when it comes to grading students, Franco said, but leaves it up to the teachers how to do so.

Some districts have also cut “classroom participation” from their grading criteria.

“We don’t think it’s appropriate — and we haven’t really thought it was appropriate in the past — to say, ‘your grades are going to be based on how much you participate, how often you raise your hand,’” said Duffy of West Contra Costa. “We want this term to be as much about mastery as possible, and all of these extenuating circumstances that are happening right now should not be a factor in your grade.”

San Francisco Unified had already cut participation and other “elements that are not a direct measure of knowledge and understanding of course content” from teachers’ grading criteria in 2017, spokeswoman Laura Dudnik said. Those factors include attendance, effort, student conduct and work habits, according to the policy. The district still encourages teachers to give feedback on those factors, though, Dudnik said.

As reports come in about students’ doing worse this fall than last, at least as measured by grades, districts may have to reconsider their grading policies, or at the least use the information to come up with strategies to more directly address why more students are failing.

Susan Brookhart, professor emerita at Duquesne University and author of several books on grading and assessment, said “learning-focused practices” such as removing participation and other assessments of student “effort” are essential during the pandemic, which has “shined a light” on practices that weren’t working before. She said whether a student turns in work on time or participates in class should be noted, but that the purpose of grades should be a reflection of how well they meet the standards of learning.

Two students could end up with the same level of accomplishment at the end of the year, she said, but one could take longer to have an “ah-ha” moment.

“Effort is hard to measure and easy to fake for kids who look like they’ve got pencil in hand but their mind is out the window,” Brookhart said. “It’s hard enough to observe effort accurately when teachers are face to face with students. With remote learning, you don’t see how hard they tried on an assignment.”

A bill to mandate use of the method will not advance in the Legislature this year in the face of teachers union opposition.

Nearly a third of the 930 districts statewide that reported data had a higher rate of chronic absenteeism in 2022-23 than the year before.

The move puts the fate of AB 2222 in question, but supporters insist that there is room to negotiate changes that can help tackle the state’s literacy crisis.

In the last five years, state lawmakers have made earning a credential easier and more affordable, and have offered incentives for school staff to become teachers.

Comments

Comments Policy

We welcome your comments. All comments are moderated for civility, relevance and other considerations. Click here for EdSource's Comments Policy.