A debt relief effort offered by the Small Business Administration as part of the original stimulus package contributed to a recent spike in loans made under the agency’s traditional programs.

The initiative — where the agency covers six months of principal, interest and fees for any 7(a) or 504 loan that was on the books or disbursed in the six months ending Sept. 27 — could also be masking credit quality issues in lenders’ SBA portfolios, industry observers said.

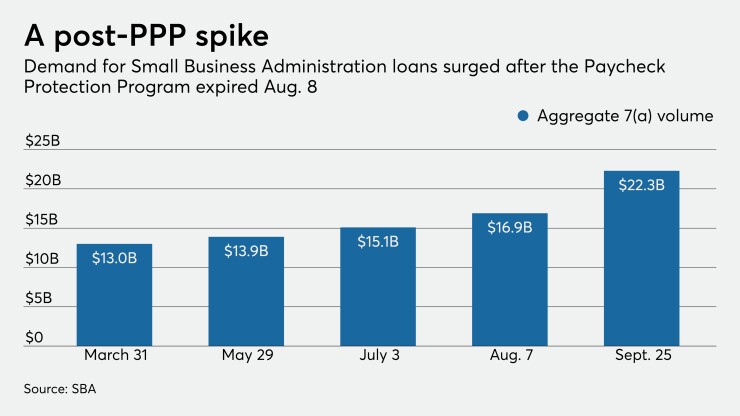

The six-month coverage, along with the Aug. 8 closure of the Paycheck Protection Program portal, incentivized lenders to flock back to 7(a) lending in recent weeks. Total 7(a) volume for fiscal-year 2020 jumped by 31% between Aug. 8 and Sept. 25, according to the most-recent data from the SBA.

“There was a tremendous incentive for businesses to get their loans fully disbursed” by the cutoff date, said Jim Fliss, national SBA manager at the $171 billion-asset KeyCorp in Cleveland. Key, among the nation’s busiest 7(a) lenders, had “one of its best months ever” in September.

“We saw that exact same spike,” said Michele Vervlied, the government guaranteed lending operations manager at the $18 billion-asset Customers Bancorp in Wyomissing, Pa. “Since the beginning of the third quarter clients have come back to us ready to make moves, looking for additional financing.”

The eleventh-hour surge in activity helped 7(a) volume for fiscal 2020 narrow the gap with the prior year. While full-year data isn’t available — the fiscal year ended on Sept. 30 — total volume on Sept. 25 was $22.3 billion, a 3.8% decline from a year earlier.

The recent increase mirrors the pop in SBA lending that took place when Congress intervened during the 2008 financial crisis. Total 7(a) volume jumped by 58% in fiscal 2010 from a year earlier, to $19.6 billion, after Congress temporarily suspended program fees charged to borrowers and raised the primary 7(a) subsidy to 90% from 75%.

Expiration of the Paycheck Protection Program not only made the six-month coverage for 7(a) more attractive, it allowed bankers to refocus on traditional programs after a period where they handled a flood of PPP applications.

“It’s fair to say there was an all-hands-on-deck, laser focus on PPP,” Fliss said. “You couldn’t do over a quarter of a century of typical SBA volume through the [PPP] in a matter of weeks and still expect business as usual.”

The status of existing 7(a) loans, in terms of credit quality, is unclear.

A stalemate in Washington over additional stimulus, along with the precarious state of the economy, has led some analysts to express concerns that SBA borrowers could have issues when the six months of coverage for their loans ends.

The coverage period just wrapped up for 7(a) and 504 loans that were on the books on March 27 when the first stimulus package was signed into law. However, loans originated near the end of the last fiscal year will be covered into March 2020.

“These government programs are, in some cases at least, delaying credit issues, not necessarily solving them,” said Stephen Scouten, an analyst at Piper Sandler. “That makes it challenging to really understand where the credit environment is right now. We’re all looking for the next signs.”

Investors should keep an eye on deferrals and delinquency data for traditional SBA loans, said Brian Martin, an analyst at Janney Montgomery Scott. Martin said it is likely some will become criticized, adding that the ultimate level could shed light on the credit outlook for small businesses across a range of sectors.

To be sure, lenders are protected against massive credit issues because the SBA guarantees up to 75% of the face value of loans made by under the 7(a) and 504 programs.

“We’re not talking about a devastating blow here, but it could be a signal of where things might be headed,” Martin said. “It will be something we think is definitely worth monitoring.”

But a surge in credit losses could create headaches for banks that look to sell the guaranteed portions of the SBA loans, said Bert Ely, head of consulting firm Ely & Co.

“I do think we’re going to see a lot of smaller businesses just close up shop” after the six-month coverage period ends, Ely said.

“This pandemic has really taken a toll on the little guys — not just restaurants but across retail,” Ely added. “I think the SBA is going have to pay up on a lot of guarantees, and banks will have to absorb some losses on their share.”

Lenders, for the most part, are more optimistic about the integrity of their portfolios.\

“Overall, we remain pretty bullish and general demand in [the fourth quarter] remains relatively strong,” Fliss said.

“Of course, we’re watching things like the payment subsidies that are going to go away,” he added. “That will potentially expose some warts. … We’ll have a lot more data and a lot more certainty once we start to see yearend financial statements.”

“We’re predicting growth next year in both larger loans and loans under $350,000,” Vervlied said. “We see the 7(a) program as an important vehicle to help stimulate recovery.”

But that isn’t stopping lenders from developing a wish list of changes they want Congress to make to bolster 7(a) as the economy starts to recover. For starters, they want the traditional subsidy bumped back up to 90%, along with waiving guarantee fees.

Lawmaker “should consider the tried and true temporary changes to the 7(a) loans to further support stimulus and economic recovery,” said Greg Clarkson, the SBA division manager at the $102.3 billion-asset BBVA USA in Birmingham, Ala.

“When you get into these recessionary environments, having additional comfort allows us to do more to help clients,” Fliss said. “That’s the intention of the program. To help us get comfortable and give our clients access to capital at more favorable terms.”