Advertisement

With An Eye Toward Net-Zero Emissions, Mass. Officials Propose Roadmap To 2030

Massachusetts is already committed to eliminating its net carbon emissions by 2050 — but that's a long way off. So as 2020 draws to a close, state officials are proposing an interim goal: to shrink the state's carbon footprint down to at least 45% of its 1990 level in the next decade.

The state's old habits of transportation, home construction and energy generation would have to change — some profoundly — to meet even that target by 2030.

But officials say it can be done with help from businesses and neighboring states, and without putting too much strain on an economy still reeling from the COVID-19 pandemic.

The state's Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs (EEA) released this interim plan, alongside a "2050 Decarbonization Roadmap," on Wednesday, adding detail to the decarbonization commitment that Gov. Charlie Baker made in January.

EEA Sec. Kathleen Theoharides said that any emissions reduction of at least 40% will keep Massachusetts on track to meet its net-zero commitment on schedule — but that some "balance" is required.

"There is a real risk, with going beyond 45%, that it would be unnecessarily disruptive to the economy — particularly for the people who can least afford it," Theoharides said.

Many of the changes the state considers in the interim plan published Wednesday will be costly: like retrofitting a million homes and 350 million square feet of commercial real estate to better generate and trap heat, replacing three million clothes dryers and hot-water heaters, or adding 6,000 new megawatts in solar and offshore energy to the grid (though those costs have declined dramatically).

Given that transportation is now the leading cause of carbon emissions, Theoharides said the state should aim to phase out the sale of new fuel-burning vehicles entirely by 2035. The plan calls for 750,000 more electric cars and trucks on the state's roads by 2030, but driving less — it calls for a 15% reduction of total commute miles by the same deadline.

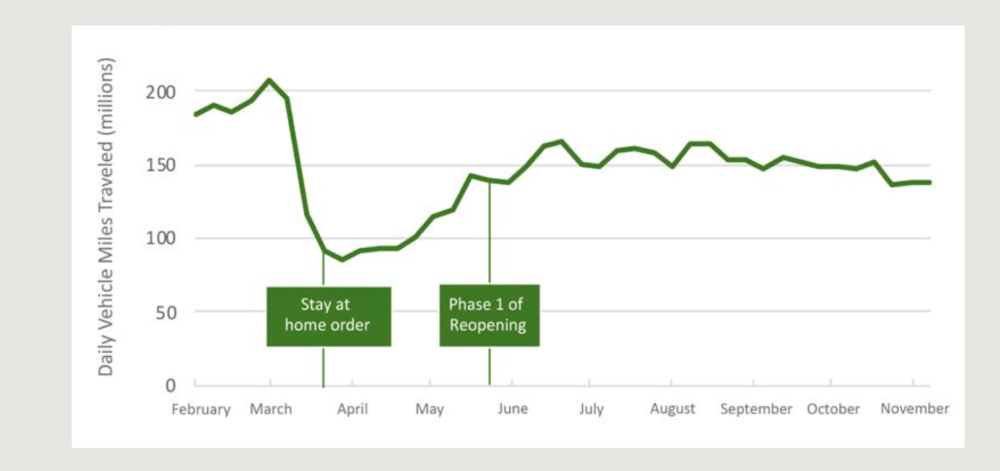

On commutes, the pandemic offered promising early results. After offices closed in March, commute miles dropped by 50%, and still have only returned to 80% of their pre-lockdown levels.

As a consequence, many business leaders came to see that telecommuting "is a viable, often very productive way to work," Theoharides said. "We actually think that 'tele-work' may be here to stay" even as the pandemic subsides — and even without the state offering financial incentives.

Many environmental advocates applauded the news — albeit with some reservations.

Jim Aloisi, the state's former transportation secretary, said the proposal should take a more holistic approach to "the transportation-emissions beast." Aloisi argued that the plan overlooked reliable, efficient public transit as a climate solution in favor of electric vehicles — which, he argued, are still costly and lack infrastructural support.

The Environmental League of Massachusetts applauded the state's roadmap in its general outlines — and specifically noting its commitment offshore wind and the drawdown of natural gas.

League President Elizabeth Turnbull Henry said the plan plotted a green future with "manageable net costs and outstanding co-benefits." But she added that, "given the urgency of the climate crisis," it isn't ambitious enough. (The group had pushed the state to set a higher interim target — of 50% emissions reduction — by 2030.)

The 45% target may sound more daunting than it is.

As of 2017, the state was already halfway there: annual carbon output down 21.5% from the 1990 benchmark. Almost two-thirds of that progress can be attributed to a much cleaner electrical grid: oil and coal, once dominant, provided for just 10% of the state's overall power in 2017.

Then again, the new staple, natural gas, adds carbon to the atmosphere, too — meaning. In particular, Theoharides hoped, offshore power stations could become the "anchor" of the 2030 electrical system, generating thousands of jobs along the way.

To meet the new goal, the state will have to rethink not just its power grid, but the dryers in people's homes and the cars in their driveways — all while knowing that many are struggling to cover the basics.

Once enacted, the 45% target will be legally binding on the Baker administration and its successor. But for now it's a proposal — Theoharides and staff are soliciting public review between Jan. 7 and Feb. 22.