As Arab citizens, we have always been surrounded by seemingly uncrossable borders and boundaries. Unless of course you have wasta—that is when you know someone that knows someone (that knows someone) who can help.

Borders between countries are the most apparent. Borders rendered invisible under the banner of the Arab world, where citizens grew up on the dream of Arab unity, a shared Arab identity through a common language, ambition, sovereignty, and self-identification. These were once common responsibilities we wanted to share. In reality, citizens of Arab League countries must obtain much sought-after visas to enter fellow Arab lands. When granted, depending on the political situation at the time, they may have to endure a less-than friendly chat with local security forces.

But borders, as a concept, aren’t confined to lines on a map—we face metaphorical boundaries, too. As children in the Arab world, we were never told or encouraged, as some American kids are, no matter how true, “you can be president one day.” Because, where we are from, this dream means you are suggesting that, at some point in the indeterminate future, our beloved leader—“elected by 99% of the population, protector of Islam, the Zionists’ worst nightmare”—will no longer rule. This can be considered seditious speech, which means some eavesdropper might report you and your family to the establishment. You will be deemed CIA collaborators, and you will need to leave the country, or else die in a mysterious “plane crash.”

I exaggerate, of course. But not much.

As young adults, we also face boundaries in our educational and professional ambitions. Our parents insisted on the continuation of their legacy: we must continue to be afandi—distinguished and educated men, a title given to us by the Ottomans and later used by the British. In simpler terms, we were told to acquire a safe job in government, one that comes with a title that you can keep until you die. Or work for a foreign company—do what your Western boss tells you to do, and avoid creativity. Keep your head down. If you are a creative, however, this must remain a hobby. Preferably a secret one.

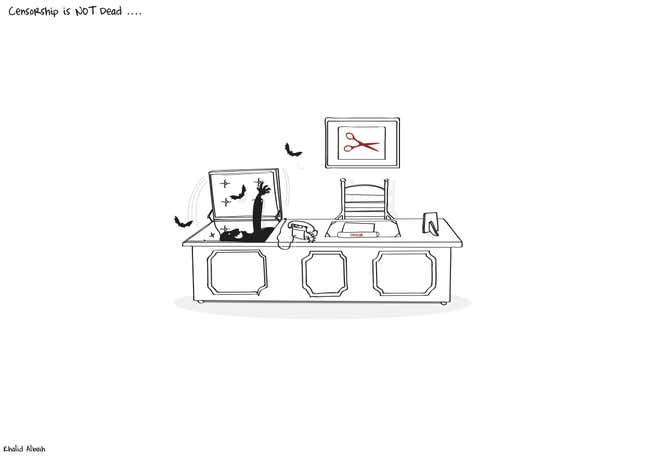

In this information age, we are also blocked by boundaries in our fight for access and free expression. We are censored in what we watch, read, write or even draw. (I am a political cartoonist.) Usually, these boundaries are set by someone whose job it is to decide limits on our behalf, declaring what is “safe” for adult consumption as if we are actually children. Our leaders attempt to placate us with poor imitations, a watered-down web.

These arbiters of propriety might unsophisticatedly edit out a kiss between leads in a romantic film because, in our conservative societies, the youth will surely be corrupted by these images. They might even try to imitate them! (Little do they know, they see much more on porn sites accessed through VPN gateways.)

The list goes on: should a Western news site report damning information—veracity is irrelevant—of what our royal families or government officials have been getting up to overseas, it is summarily blocked. Books containing atheistic or liberal ideals are banned, too. Better yet, the liberal-atheist writer himself! The children must be “protected” from the social reality; the state will seize newspapers that pose an ideological threat. It’s the same, old story.

In this region, these boundaries are all-too familiar to us. But looking to the West—the home of so many so-called freedoms—we see boundaries, too.

Google and the NSA are reading your emails, tracking your clicks, deciding how much traffic a site gets, controlling which news reports go viral, and which outlets are throttled. International publications shelter American readers. The CIA and major press can get too cozy for comfort. Western censorship is more subtle—relying on collusion between people, corporations, and the state.

Those in the Arab world, including myself, tend to approve of some degree of censorship. This is due to a kind of contrived, public politeness or political correctness as imposed by deep-rooted socio-religious factors. I am not suggesting that it’s right, and I’m not suggesting it’s wrong either. But we acknowledge its existence—which is more than I can say for some parts of the West.

After all, the most effective boundaries, in my opinion, are the ones we impose on ourselves. With self-censorship, we are silencing ourselves. And silence is no better than lying, albeit by omission. In the words of the Russian poet Yevgeny Yevtushenko, “When truth is replaced by silence, the silence is a lie.”