You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The growing public focus on student loan debt in recent years has been driven by some numbers that really matter (like the passing of the $1 trillion threshold in the amount of total outstanding loan debt) and some that are less meaningful (anecdotal reports about the occasional baristas who accumulated $120,000 in debt, an outlier level when the average is about a quarter of that).

Exactly which data points tell the true story about the seriousness of the student debt crisis is to some extent in the eye of the beholder. But Mark Kantrowitz, one of the country's sharpest analysts of student aid, offers one way of looking at the issue in a new paper. It strives to define what unmanageable or “excessive” student debt looks like (as many others, including the Obama administration in its gainful employment regulations, have before him), and then uses the best available data (imperfect as they are) to gauge how many have it.

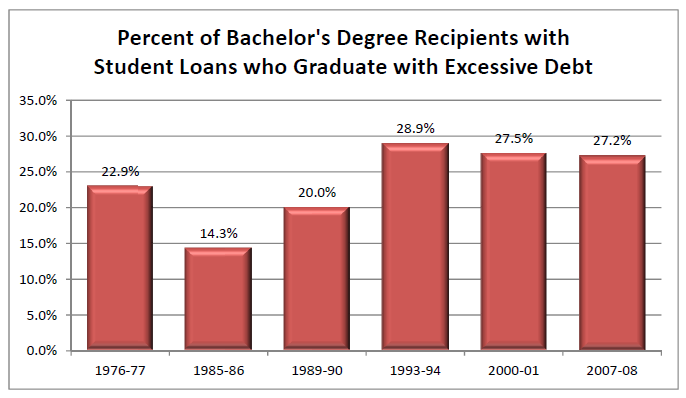

Kantrowitz finds that the proportion of undergraduate student loan borrowers who are graduating with debt he defines as excessive (having to spend at least 10 percent of their gross monthly income on debt payments) has actually stayed fairly constant over the last two decades, at roughly one in four. That's the good news.

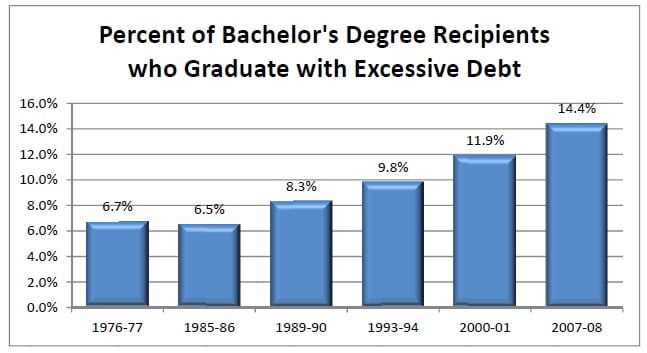

The bad is that the proportion of all graduates who had to borrow to pay for college has risen steadily, resulting in a meaningful increase in the proportion of all graduates who meet the excessive debt threshold -- to 14.4 percent in 2007-8, up from 11.9 percent in 2003-4 and 9.8 percent in 1993-4, according to data from the federal government's Baccalaureate and Beyond longitudinal study. Students in certain low-paying fields (theology, communications and agriculture, for instance), women (who typically earn less than men), and low-income students are likelier than their peers to have excessive debt, Kantrowitz finds.

Digging Deeper

Kantrowitz, a consultant and financial aid analyst with a particular expertise in data crunching (given degrees in math and computer science from MIT and Carnegie Mellon), does two main things in the paper: makes the case for his definition of excessive debt, then applies the definition to the pool of borrowers.

Much of the current discourse about student borrowing -- driven by horror stories of outliers with six-figure debt and eye-popping national debt figures -- suggests that student debt is an unequivocal problem, to be avoided if at all possible. But as the Obama administration did in its gainful employment rules, Kantrowitz argues that looking at the amount of an individual's debt alone tells us little, since it provides no context for whether a borrower can repay it.

“Six‐figure student loan debt might be excessive for a borrower with just a bachelor’s degree in a low‐paying liberal arts field, but not for a borrower who earns an advanced degree, such as an M.D. in a lucrative specialty like oncology, cardiology or orthopedics,” Kantrowitz writes. “To determine whether the student loan debt is affordable, the monthly loan payment must be compared with monthly income.”

Examining census and other historical data, Kantrowitz concludes that “student loan debt at graduation should be considered affordable if the monthly loan payments assuming a 10‐year repayment term are less than 10 percent of gross monthly income …. The student loan payments will still be affordable, but more of a financial stretch for the borrower, if the payments are less than 15 percent of gross monthly income.”

While it might be logical to expect that more borrowers are graduating with ever-increasing amounts of debt, that doesn't appear to be the case, Kantrowitz finds. As seen in the chart below, the proportion of undergraduates who graduate with debt has stayed the same (and even roughly declined) since the early 1990s, according to the last three versions of the federal baccalaureate survey. (And it wasn't much lower in the mid-1970s, though it dipped in the intervening 20 years.)

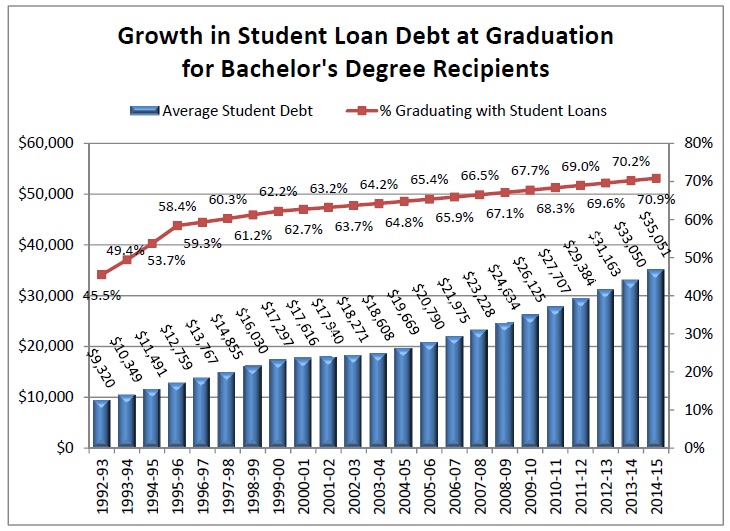

What has gone up, though, is the proportion of all students who borrow to finance their undergraduate educations, and the amount they borrow, as seen in this chart -- the former rising to its current 71 percent by an average of a point a year since the early 1990s, and the latter nearly quadrupling over the same period, to about $35,000:

Taken together, that has resulted in about a 50 percent increase over that time (and more than a doubling going back two decades more) in the proportion of all graduates who have debt Kantrowitz deems excessive:

Kantrowitz adds one more layer of analysis, based on the Baccalaureate and Beyond survey of graduates, which the Education Department also produces. He asserts that graduates with what he deems excessive debt are more likely than others to say that:

- College was not worth it (35.8 vs. 22.2 percent)

- Student debt influenced their work plans (64.3 vs. 41.6 percent)

- They delayed buying a home (49.8 vs. 38.1 percent)

- They delayed having children (36.4 vs. 27.9 percent)

- They worked more than one job (33 vs. 23.4 percent).

Questions and Limitations

Sandy Baum, another highly respected financial aid researcher, said Kantrowitz's analysis was useful and generally sound. She noted, though, that using first-year income data is “problematic.” Since earnings generally will rise over the loan repayment period, “the counts are almost certainly exaggerated.”

Terry W. Hartle, senior vice president for government and public affairs at the American Council on Education, said the analysis deserved attention because Kantrowitz is “one of the nation’s most sophisticated and experienced analysts of student loans.”

He cited potential limitations of the data, though. Hartle noted that the latest data examine students who graduated in 2007-8, “not a good year for a new college graduate to be looking for a job.”

And numerous changes in student repayment options since then mean, Hartle said, that Kantrowitz's analysis is unlikely to reflect “the experience that today’s borrowers are facing.”

Follow me on Twitter @dougledihe.