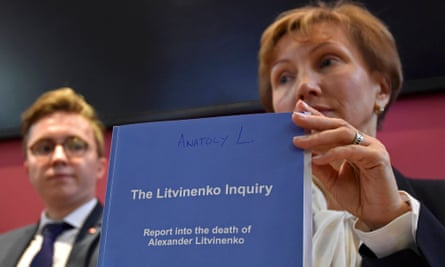

An inquiry into the assassination of Alexander Litvinenko in the heart of London in 2006 has concluded that he was “probably” murdered on the personal orders of Vladimir Putin. This is a troubling accusation.

The report (pdf) said that Litvinenko, who died from radioactive poisoning, was killed by two Russian agents, Andrei Lugovoi and Dmitry Kovtun, who were most likely acting on behalf of the Russian FSB secret service.

The head of the inquiry, Sir Robert Owen, also came to the conclusion that there was sufficient evidence heard in open court to build a “strong circumstantial case” against the Russian state.

His conclusions mirror those of the late Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky, who had been living in London waging a campaign against Putin before his own death in 2013. Litvinenko was his chief bomb thrower.

I’ve been analysing this case since Litvinenko’s death, and I’ve followed the inquiry closely. I don’t know whether or not his murder was ordered by the Russian president or anyone in the Kremlin. What I do know is that Owen’s findings are not supported by reliable evidence.

The report relies on hearsay and is marred by inconsistent logic. It offers no factual insights into what really happened to Litvinenko, yet has been taken as gospel truth by governments and pundits across the west.

Here are some of the problems

1. PR campaign

The inquiry failed to take into account the massive misinformation campaign initiated by Berezovsky. It was Berezovsky, an arch-enemy of Putin, who put forward the narrative that the Russian president was behind the poisoning of Litvinenko and fed this to a gullible western media, with the help of the PR firm Bell Pottinger.

A typical headline of the day was something like “Ex-KGB Spy Murdered on Orders of Putin”. No facts were presented, just unsupported allegations. Berezovsky’s well-funded management of the public discourse set the tone for everything that was to come.

If this had been a jury trial, the media coverage would have prejudiced the case. In the absence of a jury Berezovsky’s targets included the public, journalists, police, and government officials. Yet there was no consideration of the impact of this wide-reaching influence in the report.

2. Inconsistent

The inquiry appears to use different evidentiary standards for different witnesses. On the one hand Owen claims that he considers some of the evidence submitted by the two alleged assassins, Lugovoi and Kovtun, to be deficient. As a result, he says, he won’t regard as credible any parts of their accounts.

But he applies a different standard to others. For example, a retired physics professor named Norman Dombey testified that a polonium sample contains a characteristic fingerprint that allows it to be traced back to its source. However Owen concludes that this fingerprint theory “is flawed and must be rejected”. He does not react to problems with some of Dombey’s testimony by dismissing all of it. In fact, he says that he received valuable evidence from Dombey.

3. Unreliable

There is also the question of Litvinenko’s dramatic deathbed statement implicating Putin that drew so much international attention. Early media reports suggest the statement was composed by Litvinenko himself and dictated to his associate, Alexander Goldfarb. The inquiry report describes Goldfarb as the co-author of the book Death of a Dissident with Marina Litvinenko. It does not mention that he was a close ally of Berezovsky’s.

Later media reports quote Goldfarb as saying that he wrote the statement himself and checked it with Litvinenko. Another account suggests the statement was drafted by the family lawyer, George Menzies, and discussed with the PR firm Bell Pottinger, acting for Berezovsky.

Which is correct? And even more importantly, the statement does not explain how Litvinenko could possibly have known of the Russian president’s culpability, nor does it offer evidence to back up the allegation.

4. Bias

The report fails to acknowledge that Goldfarb is not an objective observer in this case. For instance, he was also involved in promoting the anti-Putin protests of the punk rock group Pussy Riot. This is important because it suggests that the accusations against Putin form part of a long-running campaign stretching over his entire tenure in the Kremlin.

The report recounts many allegations against him as if they were discrete events rather than seeing them as part of a continuous process. The point here is that the inquiry should have considered Goldfarb’s testimony within a context of a systematic anti-Putin agenda.

5. Lacking evidence

The report admits that there are no hard facts to support the claims against Putin, noting that “evidence of Russian state involvement in most of these deaths is circumstantial”. But “circumstantial” is used here as a euphemism for “factually unsupported”.

The report goes on to suggest that the other allegations against Putin over the years, for example that he was implicated in the murder of the journalist Anna Politkovskaya, “establish a pattern of events, which is of contextual importance to the circumstances of Mr Litvinenko’s death”. In other words, Owen admits to being influenced by unproven cases in his consideration of culpability in Litvinenko’s death.

6. Dubious reasoning

The role of Mario Scaramella, an Italian sometimes described as an academic, presented a dilemma for the inquiry. At first Litvinenko publically accused Scaramella of poisoning him to stop him disclosing information about Russia’s culpability in Politkovskaya’s death. But the story seems to have changed after Berezovsky visited Litvinenko in hospital, after which his people began saying that Litvinenko had blamed Putin.

There is no evidence that Scaramella was responsible, but the inquiry accepted a strange reasoning for Litvinenko implicating him in the first place. Apparently the former spy was embarrassed to admit that he hadn’t seen Lugovoi and Kovtun as threats, so initially concocted the allegations against Scaramello to salvage his professional pride.

While this analysis points to serious flaws in the report, it does not present evidence to exonerate Putin. As I said, I don’t know whether or not he is to blame. But what happened to the presumption of innocence and the need to build a case before declaring someone guilty?

It is clear that those who are behind these claims against the Russian president have an agenda, and are using a wealth of means in their attempts to convince others.

The public inquiry’s acceptance of so many of their questionable allegations casts a pall over Owen’s efforts and renders his report practically useless.

William Dunkerley is a media analyst and author based in the US, who has written extensibly about Russia. His recent books include Litvinenko Murder Case Solved and The Phony Litvinenko Murder